Fashion today is all about finding your personal style. Mixing, matching, and accessorizing to create the perfect look for any occasion has never been easier or more affordable. Ready-to-wear fashion in every rainbow color customizable for the perfect fit beckons from glossy magazine covers and glazed shop windows. And, if that’s not convenient enough, the modern fashionista can stay informed of the latest styles, scroll through online racks, and curate her wardrobe from the comfort of home.

“…one fad was literally worth dying for.”

Just within the last few hundred years, fashion has emerged out of its roughly woven past in the soft comfort and brilliant color of modern design. The simplicity and ease of stepping out in style is so simple, it’s easy to forget how complicated it once was. While fashion is all about “killing it,” one fad was quite literally worth dying for.

In our modern world of design, a designer’s creativity knows no limits. Textiles in every texture, weave, and hue. Hand-twisted and hand-loomed linen and cotton tunics were the staple of every ancient wardrobe, while today’s fabrics present every possible combination of natural and synthetic fibers for comfortable, functional design.

Patterned design options have also come a long way from the hand-painted, embroidered, and block-printed textiles only the wealthy could afford. The most important change, however, is in the dye.

For thousands of years, dyeing fabric was expensive. Finding plant or animal-based inks and pigments was no easy task. Some dyes came from crushed bugs like the scarlet worm, producing a rich red stain. Squid ink, crushed abalone shells, powdered minerals, and vegetable dyes made from non-indigenous species were either costly or simply unavailable to the masses.

It wasn’t until the Industrial Revolution of the late 18 century that chemically produced dyes made a colorful splash across the textile landscape. As factories began to churn out waste products in beautiful chemical colors, a new dyeing method was born.

These original chemical dyes were completely untested and unregulated for humans. They were cheap, produced vibrant colors compared to exotic plant and animal dyes, and were readily available.

“It earned these women in green gowns the title of “femme fatales.””

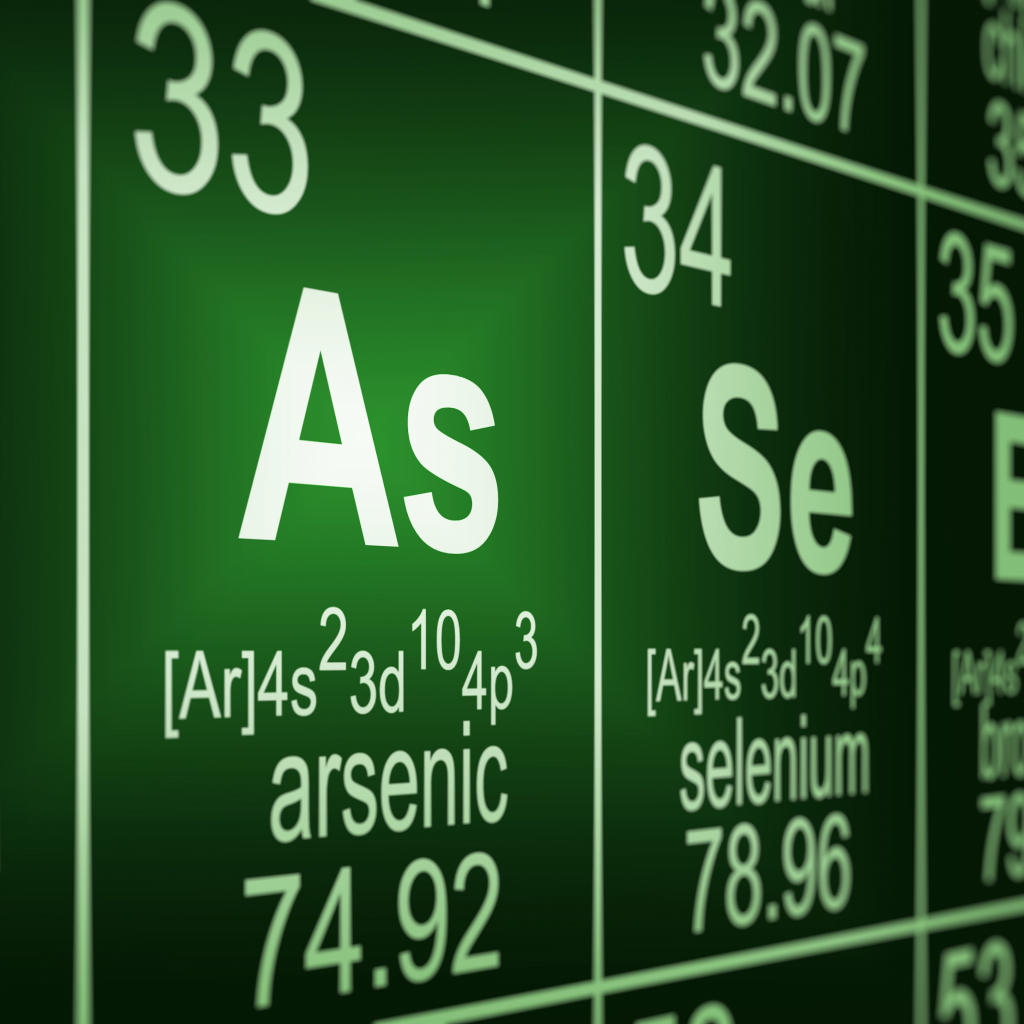

One such dye came from “white arsenic,” or arsenic trioxide mixed with copper. Invented in 1778 by a chemist named Carl Scheele, this “color-fast” dye quickly turned the fashion world green. This new-fangled and easily accessible powder produced a deep rich viridescent hue. Coloring everything from faux leaves to silk gowns, arsenic green quickly caught the eye of the fashionably inclined.

At first, the effects of this fallacious fad went unnoticed. 18th-century men courting women adorned in fashionable green gowns experienced symptoms like red eyes, vomiting, and convulsions. While these symptoms were chalked up to nothing more than lovesickness, it earned these women in green gowns the title of “femme fatales.” The death of a 19-year-old flower maker, Matilda Scheurer, finally attracted the right kind of attention.

Informing the brightly bepainted public of the dangerous side-effects of chemical dyes was no easy task. They were unconvinced that this new-fangled dyeing method was to blame. Soon, philanthropic women’s groups and medical journals began investigating faux flower factories and the viridescent gowns of those unfortunate enough to be leading ladies of Victorian fashion. Many were still skeptical, and a few literally turned green at the idea that a white powder used in everything from rat poison to medicines could be harmful.

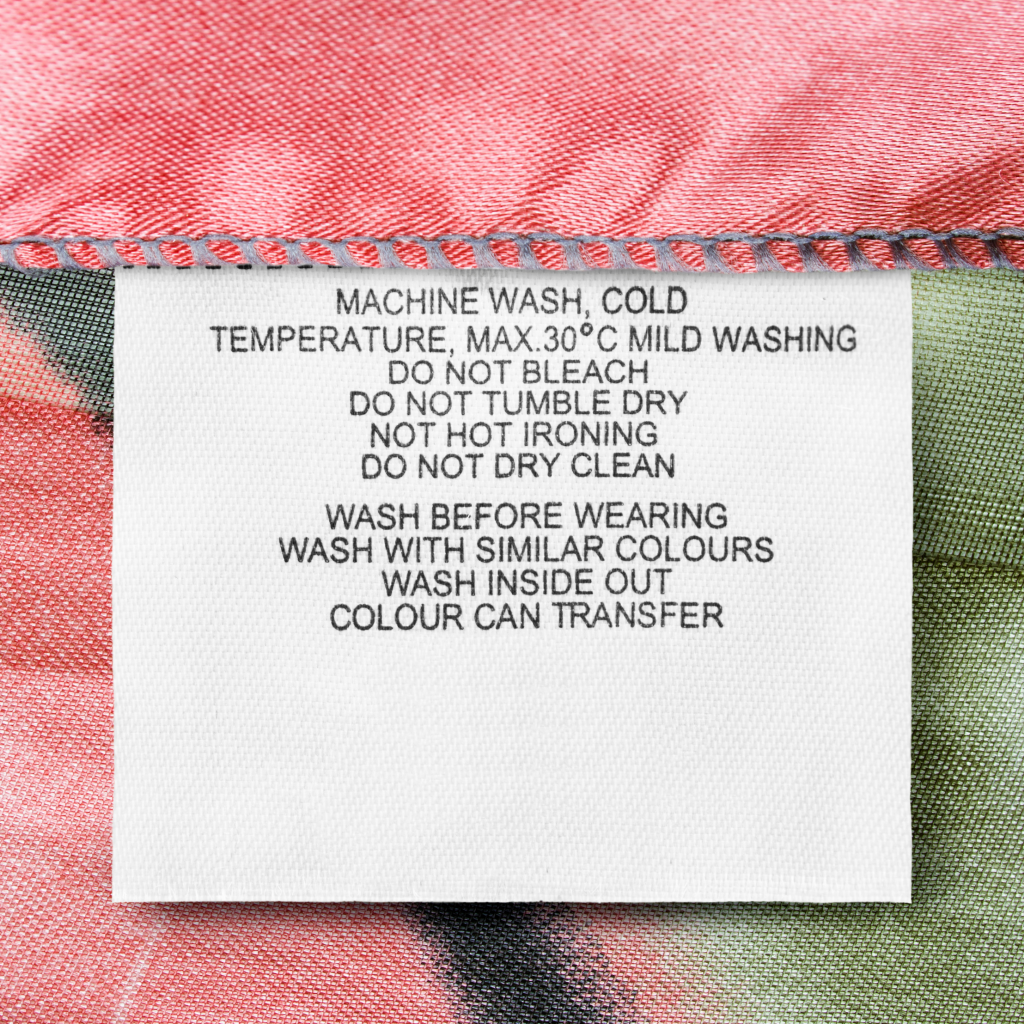

Today, the humble label is an unassuming memorial to those unsung heroes who fought for the truth. A quick glance provides the consumer with life-saving information on fabric content, dyes, and garment care. The days of flammable and fatal fashion are hopefully behind us, thanks to those few who cared enough to know more.

The lesson here is quite simple. In an age of unprecedented progress and revolution, the old adage may yet prove untrue that “every fault is a fashion.” We can, however, learn from the past to design a better future. And, in the event that history repeats in whatever multicolored patterns it chooses, always read the label first.